This third article in a series about our visit to the U.S. Mint at Denver offers information, photos and videos on how it makes dies to strike coins.

Walking through the United States Mint die floor in Denver, Colorado is kind of like peering through a window of a bakery or candy shop that shows how its treats are made. There’s a feeling of enchantment as things move around from place to place and take their final shape.

More than 6 billion coins for circulation came from Denver in 2013. That’s about 19 coins for every man, woman and child in the United States. All were made from coin designs on dies mounted in presses. Dies sandwich blank metal discs under high pressure to create coins, much like Play-Doh toys compress dough into unique shapes.

Cutting Steel Bars, Creating Die Blanks and Inspecting Them

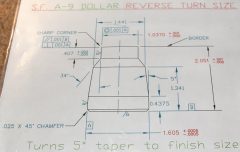

Dies are made from steel. For the technically interested, either A9, 52-100 or L6 steel is used, with the type determined mostly by the coin to be made — pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, etc., and with some consideration as to whether the coin is for circulation or numismatic purposes.

|

|

To get die blank stock, cylindrical steel bars of about 12′ in length are cut into smaller 3” sizes by a machine that slices like a sharp knife into summer sausage. A CNC (Computer Numerical Control) lathe does the work based on the programmed specifications of the intended coin it will strike. It grabs bars from a connected feeder, makes a flat cut at the three-inch length, and makes the other end cone-shaped. The now shorter piece of steel is officially a "die blank."

There are many robotic arms and conveyor systems throughout the Die Shop. One of the biggest ones picks up die blanks from the cutting lathe and delivers them to a machine named Thielenhaus. It spit shines a die blank in about 2.5 minutes using a lubricant and three different tapes — rough, polish and finish.

Here are two videos of Thielenhaus in action. The first video shows a die blank that was placed onto Thielenhaus’ conveyor system by the yellow robot. The die moves along the conveyor, gets picked up and waits for an already polished die to get removed so it can get washed. The second video, perhaps more interesting, shows Thielenhaus polishing a die blank.

Now smooth and shiny, die blanks are manually moved to an inspection area. Here, machinists use microscopes to look for imperfections and RA Surface Profilometers to check for smoothness.

|

|

Hubbing Operation

The Hubbing department, in a climate-controlled clean room, is where die blanks are pressed with designs to become coin dies. Of the four United States Mint production facilities — West Point Mint, San Francisco Mint, Philadelphia Mint and Denver Mint, two share the task of hubbing.

Everything kicks off in Philadelphia where artists create coin designs. Whether sculpted in clay or in ZBrush software, designs are captured digitally and processed by the Philadelphia Mint’s unique CNC milling machine, the Mikron HSM 300 Mold Master. The Mold Master with is digital information uses a carbide tip to cut a coin’s design onto the end of a die blank, creating a "master hub."

At this point, the process turns manual as several generations of hubs and dies are created, keeping the designs true to the original. Using a 600-ton hydraulic press, the master hub’s design is pressed onto several other die blanks to produce "master dies." A single squeeze of the press creates each master die, with the pressure so great that the cone-shaped end of a die blank flows like putty to take on the master hub’s design.

Master dies are created exclusively at the Philadelphia Mint and shipped to other facilities. The Denver Mint receives them for both Denver- and San Francisco-intended coinage. There, and using the same style hydraulic press, a master die is pressed against die blanks to make "working hubs." Finally, these in turn are used to create "working dies."

Here is a short video that shows the slow squeezing action of the Hubbing Press as it makes a working die.

After each working die is inspected, it travels through additional manufacturing processes before getting mounted in a Denver Mint coining press or shipped to the San Francisco Mint for polishing and to strike its collectible proof coins.

Shaping Dies

After hubbing, working dies need to lose weight and take a specific shape so they can fit precisely into coining presses.

Until 2013, it took three operators and three sequentially working lathes to taper dies. Then, failure or errors in any one area gummed up the work across the entire job, wasting labor and time.

Enter the Okuma LT2000 EX horizontal lathe with its twin spindles and four-axis operations. It not only replaced the three older sequential lathes, it improved die quality, sliced die tapering time, greatly reduced the scrap rate and saved on labor.

Directly below is a video taken of an informational monitor on the lathe which shows what’s happening to the die.

The newer lathe is just one part of the picture. The entire die manufacturing process changed with the Mint’s implementation of the "Three-Operation Lathe Cell Manufacturing Process."

That sounds a bit complicated but the result isn’t. Mentally, picture a baseball diamond with a horizontal lathes on first, second and third bases. On the pitcher’s mound stands a big robotic arm and on home plate sits a short inbound and outbound conveyor system.

To get things moving, a machinist on "home plate" adds non-shaped dies to the inbound conveyor. A die moves on the conveyor until grabbed by the robotic arm, which takes it to one of the three waiting lathes. When any of the lathes complete a job, the robot knows. It pulls the shaped die and places it on the outbound conveyor for the return trip home. It’s a nifty process to watch. For extra background on how everything works, read this article from Manufacturing News.

|

|

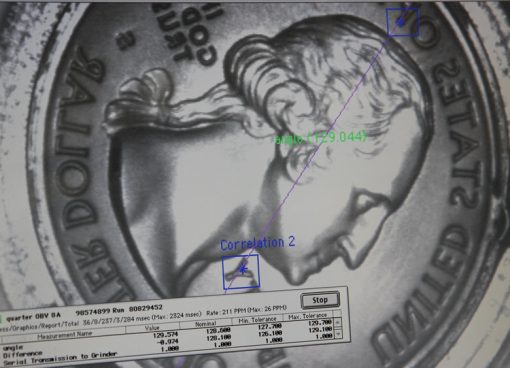

Inspections happen throughout the die manufacturing process. One inspection point is right after the dies have been tapered, with each measured according to the specifications of their intended use.

Engraving Serial Numbers on Dies

Once hubbed and tapered, coin dies become controlled items. Each is given a unique serial number for tracking throughout its lifetime. A machine lasers the numbers on the die’s side.

In this photo, Sean Calhoun operates the laser serializer machine that has been in operation at the Denver Mint since 2012. Immediately following is a video showing what it looks like when peering through the machine’s small window as the serial numbers are burned on the dies.

Die Heat Treatments for Hardening and Tempering

Dies must handle an enormous amount of stress to strike coins. For example, it takes 50 tons of pressure to create one nickel. A display in the Philadelphia Mint Public Tour visualizes that best, showing how the pressure is equivalent to the weight of about 16 elephants or the impact of 3 high-speed trains. Even more tonnage is needed to strike quarters (60 tons), half dollars (120 tons) and $1 coins (85 tons).

To harden dies and improve their resiliency, they are heated in special furnaces and then tempered in ovens. For the hardening, two big furnaces are used at the Denver Mint. One, shown immediately below, is more state-of-the-art. It’s an atmospheric vacuum furnace that runs with solar power and uses air to quench dies instead of oil. It also uses nitrogen instead of oxygen.

The other is an older vacuum batch quench furnace (VBQ) that is scheduled for replacement this year. In this furnace, dies are heated from between 1550 – 1900°F degrees without oxygen to prevent discoloration and oxidation. To cool the dies, they are dunked into oil which enables their hardness.

Dies then go into a tempering oven at around 400°F for about 5 hours. This process changes the granular structure of the dies, improves their resiliency, and stops them from chipping. Without tempering, dies would crack due to internal pressure.

Die Grinding

When dies are first shaped they have a small amount of extra material called grinding stock. This extra material is needed because dies swell and grow after hubbing and heating, but usually more up top than on bottom.

A Granger die grinding machine grinds dies after heat treating to the correct shape and size and is also used to ensure correct beam alignment.

This photo shows how a camera is used to orient dies for the locational flat, which is a flat side of the die so that the heads and tails line up. Only a 1/2 degree of error is allowed.

Notice the finger rods below. Those are "in process gauging," which means that the die’s size is adjusted to the correct shape as its lubrication, dust, and grinding processes happen. There is a 1/20th of a hair precision, or 0.0002 inches.

After grinding, once again the die is inspected and measured.

Inspecting, Hard Cleaning and Polishing Dies

Dies are inspected one last time before they are stored until installed in a coining press. In the photo below, Evan Eagle is looking for pits, scratches and other imperfections. These are buffed in a process called hard cleaning.

To clean imperfections, special brushes and diamond paste are used. Buffing wheels provide a circulated die finish.

That’s it for this article! Thank you for visiting CoinNews.net and please come back again.

Next Article in Series About the Denver Mint

The fourth article in our several part series about the U.S. Mint at Denver was published on Jan. 13, 2014. It focused on the coining division and included many more photos as well as a few short videos showing how it makes coins for circulation. To catch up on all of the articles, there are links to them in the upper right column.

This is very interesting. I never realized the complexity and care taken to make such precise dies

Some questions:

1) Could computers copy designs from older coins and create a program to reproduce them today?

2) What is saved and what is destroyed from an old die and the process that created it?

Thanks

It appears to me that some very interesting coins could be created by some minor program changes modifying dates and mint marks – true?

How are we protected from such an illegal process?

How long can the die head be in use before the image becomes too worn? i.e. number of cycles before “failure”.

Can someone purchase one of the old worn out dies to have as part of a coin collection. Since they are no longer able to be used properly does the mint ever offer the broken pieces to collectors. While I understand the possible misuse, there must be a way to create a product that can be sold before they are completely destroyed.