Two of the rarest and most famous US coins have been brought together under a single owner.

The 76-year-old coins look like regular Lincoln Cents from the era — bronze with the 16th president on one side, wheat ears on the other. Yet they were not supposed to exist. For years, US Mint officials claimed that they didn’t.

The teenaged boys who found them in the 1940s, one on the West Coast, one on the East, struggled to have them declared genuine and kept them their whole lives. The coins were sold after their deaths for more than $200,000 — each.

What makes such ordinary-looking coins so valuable? As in most things, it’s their rarity.

Some 1.1 billion Lincoln Cents were minted in 1943. But all of them were supposed to be struck in steel because the copper that normally made up 95% of the one cent coins was needed to make ammunition during World War II.

Yet rumors quickly began circulating that a very few 1943 Lincoln Cents had been made of bronze blanks left over from the previous year and that they were very valuable if you could find one. One rumor said Ford Motor Co. had offered a new car for one. That rumor proved to be untrue, though it was so widely spread that Ford and the US Mint were hard-put to answer the flood of mailed-in inquiries about it.

Ads ran in comic books and magazines as late as the 1950s offering $10,000 for one of the coins.

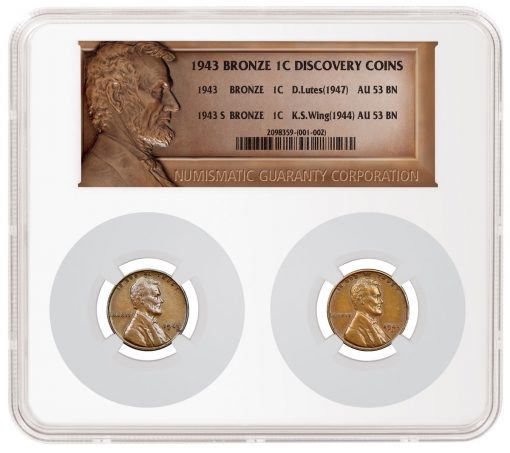

The Don Lutes Jr. 1943 Philadelphia Bronze Lincoln Cent and the Kenneth S. Wing Jr. 1943 San Francisco Bronze Lincoln Cent, each named for the teenaged boys who found them more than 70 years ago, were both certified as authentic by Numismatic Guaranty Corporation® (NGC®), a leading third-party authentication and grading service for collectible coins. NGC graded them both AU 53 separately. Now the two coins are displayed together in a single tamper-evident NGC holder.

To the man who brought them together, Concord, Massachusetts, coin dealer Tom Caldwell, the coins’ rarity, well-known stories and common-man appeal are what make them so attractive.

"These are coins that your neighbor knows about, not just hard-core collectors," said the owner of Northeast Numismatics for 40 years.

"People love provenance, and the stories of these two coins are so well known."

A 1943 Bronze Cent was first offered for sale in 1958, realizing more than $40,000, according to the US Mint. In 1996, a 1943 Bronze Cent was bought for $82,500. In 2010, a 1943-D Bronze Cent was sold for $1.7 million. That coin was especially rare — it is the only one known that was struck at the Denver Mint.

Only around 40 1943 copper–alloy cents are known to exist.

"The 1943 Bronze Cent is by far the most famous US Mint error," says Mark Salzberg, NGC Chairman and Grading Finalizer. "Examples are extremely rare and highly coveted by collectors."

Discovery coins

The Wing and Lutes coins both are what’s known among coin collectors as "discovery coins" — the first of their kind ever found and made known. One was minted in San Francisco, as indicated by an "S" mintmark. The other one does not have a mintmark, which indicates it was struck in Philadelphia.

But what of the discoverers? Wing was 14 in 1944 when he found one in Long Beach, California. His parents had been buying him rolls of one cent coins because he was collecting sets of them.

Lutes was 16 when he found his in change he received from buying lunch at his high school in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

The young men spent years trying to get the US Mint to acknowledge that the coins were genuine. Wing finally succeeded in having his authenticated by Smithsonian Institution experts in 1957; Lutes’ was declared genuine by well-known numismatist Walter Breen in 1959.

Caldwell said he heard in the summer of 2018 that the coin that belonged to Lutes, who died in September 2018, was coming up for sale in January 2019. He purchased it for $204,000.

"We’d just sold a ’43 Bronze Cent of a slightly lower grade, so we had some idea of the market," he said. "We were not expecting to buy it but were fortunate that we could get it at a reasonable price."

Then the cent once owned by Wing, who died in 1996, was offered at auction in August 2019.

"We bought it, again pretty reasonably, and put the two together in a single NGC holder," Caldwell said. He paid $216,000 for the Wing coin.

The stories of how the coins were found were appealing. The sums for which they were sold this year caused them to receive coverage from the news media — even the non-numismatic ones — with headlines like "Coin found in lunch change fetches a pretty penny."

The sales, particularly of the Lutes coin, were the subject of feature stories done by CNN, the New York Post, the Boston Globe, USA Today, and Newsweek and Fortune magazines, among other news outlets.

Now that the two coins are displayed in the same holder, Caldwell said he plans to display them at a few regional shows, then at the FUN show in Orlando in January and the Long Beach Expo show in California in February.

The pair will be sold eventually, Caldwell said. Now that they are together, he will not split them up.

For more information about Northeast Numismatics, go to northeastcoin.com.

For more information about NGC and its grading services, visit NGCcoin.com.

What is interesting is that the 1983 copper cents, also made by mistake from leftover planchets, cost only a fraction of these. I suppose it’s the idea that all should have been steel that is more exciting. Certainly it’s easier to see. (While the 1944 steel cents get some more value they just don’t seem to have the romance of the ’43 coppers.)

Well said. It’s odd that some coins seem to acquire a “cachet” while other, similar issues languish. Years ago I picked up a few late-date, low-mintage, but apparently ignored Liberty Seated coins in the hope they might eventually pop. Well, they at least look nice 🙂

FWIW, apparently a few analogous “wrong planchet” coins were minted in the mid-60s when the Mint was striking 1964-dated silver coins in parallel with 1965 and ’66 clad coins. However I’m not familiar with what they might have brought at auction.

Thanks Munzen. The ’65 silver quarter and half go for surprisingly low prices according to this: https://coins.thefuntimesguide.com/1965-silver-quarter/ Maybe that not many must come up for auction to give a real push to the prices; they aren’t well known. Perhaps people just collected pennies more, or the difference from the ’43 steels was striking.

I agree too that it comes down to demand–a lot of the early commemorative halves have low mintages but don’t cost very much. If they were Walkers or Franklins their values would be in the stratosphere.